Florence Laura Goodenough was a pioneer in psychology and the study of gifted children. Miss Goodenough was the first to support the life span development approach in Developmental Psychology. She studied under Leta Stetter-Hollingworth at Columbia University. She was born on August 6, 1886 in Honesdale, Pennsylvania. She was the youngest of nine children in farm family (Stevens and Gardner 1982).

Florence graduated with a B.Pd. (Bachelor of Pedagogy) in 1908 from the Millersville, Pennsylvania Normal School. She earned her B.S. from Columbia University in 1920. In 1921 she received her M.A. under Leta Hollingworth, also at Columbia. During this time, she served as director of research for the Rutherford and Perth Amboy, New Jersey public schools. This position today would be considered a school psychologist. It was in the public schools that Miss Goodenough did her first research studies. Her data collected was on children's drawings (Thompson 1990).

Starting in 1921, Miss Goodenough worked with Lewis Terman at Stanford University. Terman was developing the Stanford-Binet I.Q. test for children. She participated studies of gifted children under Terman's direction. Florence Goodenough was even listed as a contributor to his book Genetic Studies of Genius, Terman 1925 (Thompson 1990). This was quite rare back then. Many graduate students would conduct the experiments, while the professor would get all of the credit. This sometimes happens today. Goodenough was very fortunate that Terman acknowledged her hard work and devotion to the project.

In 1924, Goodenough relocated to Minneapolis, Minnesota to work in the Minneapolis Child Guidance Clinic. The next year she was appointed as an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota. By 1931, she was promoted to full professor. She held that position until her early retirement in 1947 (Harris 1959).

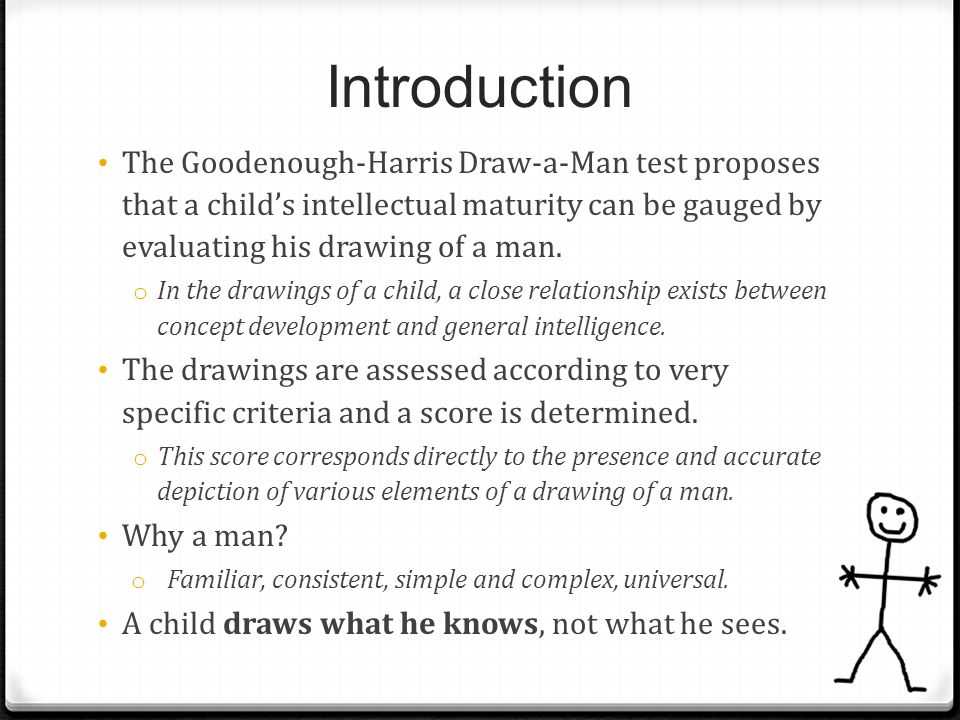

Goodenough's first book was titled Measurement of Intelligence by Drawings (1925). Until this time, nonverbal I.Q. tests were low in validity and reliability, or too long to give. Florence came up with the Draw a Man Test for preschoolers, and later, older children. Each child tested was asked to draw a man. They were given ten minutes. The test was very reliable and valid. She developed very strict criteria for rating each drawing. It also correlated well with written I.Q. tests. The Draw a Man Test was widely used until the 1950s. Florence later revised it, calling it the Draw a Woman Test. She had a sense of humor, and was always willing to recognize her faults or mistakes. She had received flack from women's and minority groups for asking children to only draw a man. Young girls may not identify at all with a "man" (Goodenough 1926).

Miss Goodenough also revised the Stanford-Binet to include smaller children. The result was the Minnesota Preschool Scale It had both verbal and nonverbal scores. She also came up with time sampling, which is studying a subject's behavior for a certain period of time. Florence developed event sampling as well. Event sampling is observing a certain behavior, and counting how often it occurs. She suggested that these methods would be useful in studying natural behavior in both humans and animals. Both methods are still used today in observational studies (Thompson 1990).

Florence was the first psychologist to critique ratio I.Q. In her 1933 Handbook of Child Psychology, she argued that the concept of mental age didn't have the same meaning for all children, and that the scores are not easy for laymen to understand. She instead thought psychologists should use percentages in reporting the results. This would allow a comparison of children of the same chronological age.

Florence published Anger in Young Children (1931), using data collected in a seven year study with forty-one children. Watson's studies on the three basic emotions of infants (rage, fear, and love) was in vogue at the time. The book reported findings that children show anger at bath time, physical discomfort, and by age four, social relations were the greatest source of anger.

One of Miss Goodenough's most famous students was Ruth Howard, the first Afro-American female to receive a Ph.D. in psychology. She served as president of the Society for Research in Child Development from 1946-1947. In 1942, she was appointed as the president of the National Counsel of Women Psychologists. Florence was never fully comfortable with this, and at one point she refused to pay her dues, and resigned, saying "I am a psychologist, not a woman psychologist" (Thompson 1990).

Florence Goodenough never married. She remained a very devoted professor and researcher. She was forced to retire early due to a physical illness. She kept writing even though she eventually went blind due to her degenerative disease. Florence Laura Goodenough died of a stroke at her sister's home in Florida on April 4, 1959 (Stevens and Gardner 1982).

REFERENCES

- Goodenough, F. 1926. A new approach to the measurement of intelligence of young children. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 33, 185-211.

- Harris, D. 1959. Florence L. Goodenough, 1886-1959. Child Development, 30, 305-306.

- Stevens, G. and Gardner, S. 1982. Florence Laura Goodenough. In G. Stevens and S. Gardner (Eds.), The women of psychology, Volume 1: Pioneers and innovators (pp. 193-197). Cambridge, MA.: Schenkman Publishing.

- Thompson, D. 1990. Women in psychology. A. O'Connell and N. Russo, (Eds.). Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press.